Priyankara Thalmedha remembers a time when you could see pods of pink dolphins cutting through the waters off the coast of Kalpitiya in north-western Sri Lanka. He was a boy then, growing up on the island of Battalangunduwa. His father was a fisherman, and the two would head out to sea together every holiday. Sometimes their path intersected with the dolphins’ route.

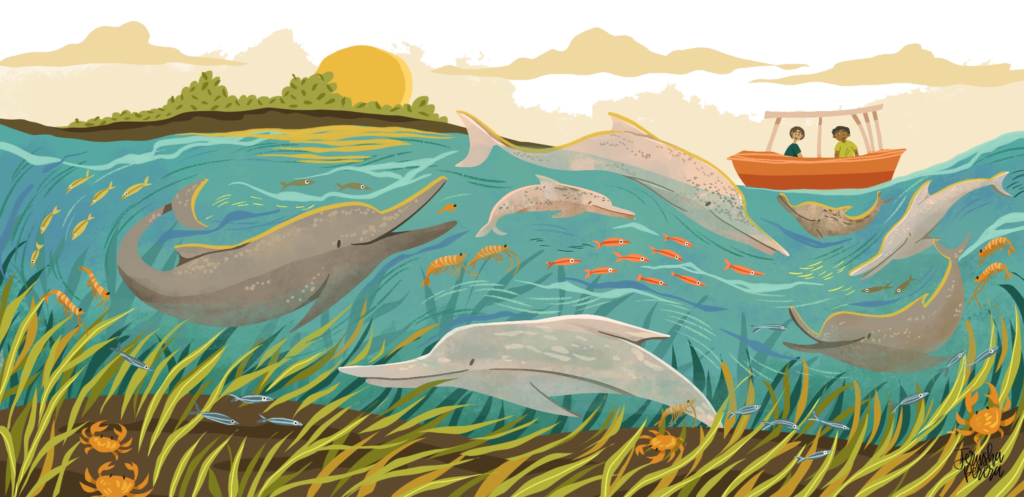

The distant forms of the pink dolphins would slowly crystallise until Priyankara and his father were surrounded, the blue ocean around filled with bodies playing or diving. More formally dubbed Indo-pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis), this species didn’t put on a show like the spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) which leapt and twirled. Some of them weren’t even completely pink, but Priyankara was thrilled to see them anyway. “Sometimes there would be over 60,” he recalls.

Today, Priyankara, who chose to stay in Kalpitiya, is the President of the Kalpitiya Tourism Boat Owners’ Association. When he gets calls for bookings, he finds at least a handful of people who have come just to catch a glimpse of the humpback dolphins. Unfortunately, they are nowhere near as easy to spot as they used to be. The last time he went searching he saw only a handful. “There were 60 dolphins when I was 12-years-old. Now I am 29, and there are only 6. I am worried I won’t see any next year,” he says.

At home in an estuary

Steve Creech, Director of pelagikos pvt ltd, was in the boat with Priyankara on that trip. Steve, who has long studied sustainable fishing practices in these waters, knows enough to head out to the Puttalam estuary. “It is the only place in Sri Lanka that you can see Indo-pacific humpback dolphins,” he explains. “They are the only estuarine dolphin species in the region.”

Since the animals prefer relatively sheltered, shallow waters, the estuary is an ideal home. It might even be the only habitat truly suitable for them in Sri Lanka. Trincomalee Bay, for instance is deeper, nor does it have the mix of brackish water that seems to best sustain the creatures dolphins feed on, mainly small fish, but also cephalopods and crustaceans.

The humpback dolphins are usually friendly and curious, and will swim close to and even under boats as they play with each other. W. Shanaka Dilshan Perera, who runs dive tours and leads boat safaris in the Puttalam estuary says finding the animals is easiest at high tide, when they’re likely to be out fishing for their next meal. However, there are no guarantees. “When people ask us to see the spinner dolphins, I can promise them that yes, 100% I will show you some, but humpback dolphins are harder to find,” he admits.

Shanaka finds himself cautioning first-time visitors that the animals look “a bit odd.” In part, this is because the dolphins’ exact colour can be hard to pin down. When they are born, they’re black, but change to grey, then pinkish with spots when they’re adolescents. Adults are grey, white or pink. That characteristic colour actually comes from a lack of pigmentation – what you see is the hue of blood pumping through vessels close to the surface of the skin.

Many don’t even realise that Sri Lanka has any pink dolphins. Perhaps the best known pods are off Hong Kong, where fisherman are known to call the dolphins Hak Kei (the Black Taboo) or Pak Kei (the White Taboo). However, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), these dolphins can be found off the west coast of Taiwan, as well as Vietnam, Thailand, and as far as Java in Indonesia in the South, and Tamil Nadu in India in the West.

Wherever you spot them, it’s that characteristic humpback that will allow for easy identification. “They aren’t graceful at all,” says Steve, pointing out that in this they’re quite unlike the fast-swimming, sleek, fun-loving spinner dolphins. Instead, these humpback dolphins take it easy. Typically, you’ll see them rest on the surface, and then duck-dive.

When diving, they linger under water for anywhere between two to eight minutes. Calves, with their smaller lungs might only manage one to three, and must surface more often than the adults. But what happens when surfacing becomes impossible?

Under siege

Priyankara has seen more than one dead dolphin. The last one he saw was adrift in the estuary, tangled in a discarded fishing net. Trapped, unable to move or to breathe, it had died.

Each such loss feels particularly significant when there are so few of the humpback dolphins left – experts say it is already unlikely that these numbers could sustain a breeding population. And the humpbacks still face more than one challenge in their immediate environment.

Fishing in the estuary has increased considerably over the last 40 to 50 years. What started out as temporary, seasonal fishing communities in the 1960s and 1970s have become established settlements now. As the population along the coastline has bloomed, so to have reports of illegal trawl net fishing. The boats drop their heavy kadippu or drag nets in the estuary, and when they pull them back in they leave devastation in their wake. The use of other harmful gear including push nets and encircling nets are believed to have damaged the once rich seagrass beds of the estuary.

Steve points out that these seagrass beds act as feeding grounds (for dugong and turtles) and nesting and nursery grounds for fish, cephalopods and crustaceans), and so destruction of this habitat is very detrimental to the entire estuarine food web that depend on it, including the humpbacks at the top. The tragedy is only heightened by how much of the trawl catch is good for nothing but animal feed.

Studies elsewhere in the region have found that increased shipping traffic also increases the risk of marine pollution; whether it is acoustic or chemical, it can harm cetaceans. Dolphins are particularly sensitive to sound, relying on it to not only communicate with each other but to forage and navigate within their environment. The boats can also leave slick trails of oil, contaminating everything they touch. “I have seen the oil on the dolphins sometimes,” says Shanaka, adding that while it’s very rare, the spinner dolphins are occasionally caught and sold in local fish markets. It is against regulations, but on islands where even a mobile signal is hard to find, it can seem impossible to enforce the rules.

Winning community support

All cetaceans are protected under Sri Lankan law. The Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, as amended in 1993, and the Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Act of 1996 make it a punishable offence not only to kill or harm them, but to sell or have possession of any part of these animals. But as Piyankara and Shanaka will tell you, in practice implementation has proved a challenge. Locals are currently largely indifferent to the humpback dolphins’ fate, and because they lack the obvious charisma of spinner dolphins not all tourism operators are invested either.

The only hope of change seems to lie in educating communities and boosting conservation efforts. The men want to see more research, and more outreach, or they worry Sri Lanka will lose its pink dolphins before it ever really appreciated them.

For his part, Steve believes enforcing laws and encouraging sustainable fishing practices will offer some respite for the few remaining pink dolphins. Fish are what the dolphins eat. To conserve them, to give them even the slimmest a chance of survival, fishing practices in the Puttalam estuary need to operate sustainably, generating benefits for both fishermen and dolphins.

“If the management of fisheries in the Puttalam estuary remains unchanged,” says Steve, “then it is unlikely Priyankara’s children will get the chance to see and delight in the pink dolphins like their father and grandfather did.”